This quarter and the last I’ve been on a bend to use up certain storage deposits located around my waist. Noom worked the best, although the chipper, chummy style of the app was so annoying that it was almost not worth it. Then I tried coming up with a home exercise routine but I never properly prioritised the time for it. Now I’m giving intermittent fasting with the app Simple a go.

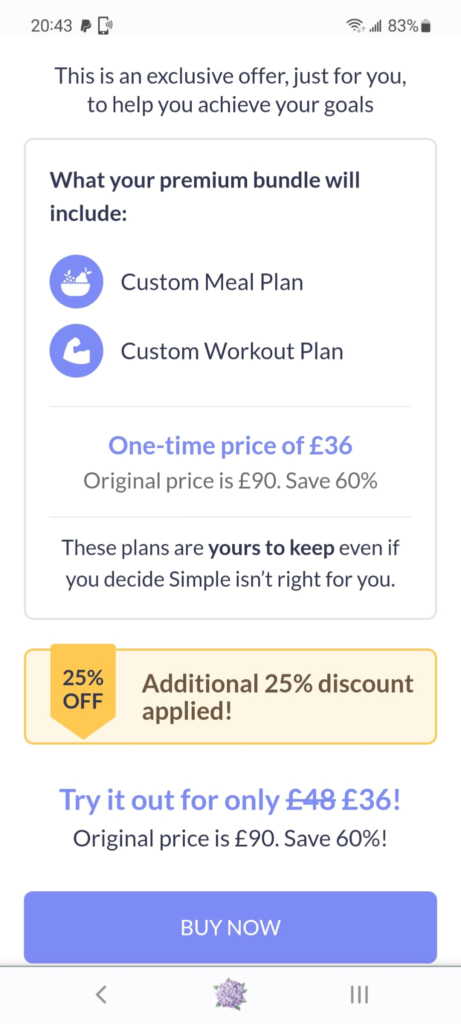

Subscribing to these apps has been pretty eye-opening. It feels commonplace now to run into offers like this one:

This was screen 5 or 6 in the sign-up process. The first one offered me a trial at £1 or to subscribe at full price, £90. I picked the trial and then got multiple screens pushing the full subscription at lower and lower prices. In the end I did buy it at £36 (cancel any time).

Yesterday must have been my lucky day because this wasn’t the only instance of scoring seemingly amazing deals. I also went to have a massage using a money-off voucher. Then I was sold a follow-up ‘assessment’ which apparently normally is £94, but for people like me who had come through the particular promotion there was a special offer of £15.

The third one was cancelling my auto-subscription to the make-up brand Il Makiage. I didn’t get a screenshot but it was a similar experience of clicking through multiple screens, each sounding more desperate than the last to keep my business, until at last – I assume – I got to the real price, which was a fraction of where I’d started. That one I skipped.

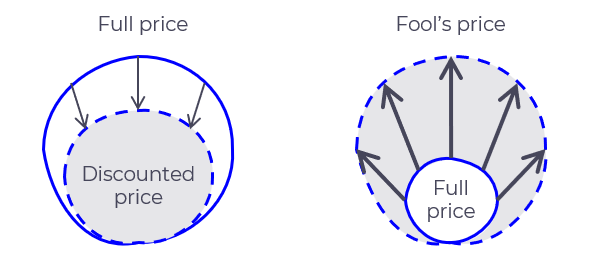

The question is whether this is just price segmentation – more brazen than before, but price segmentation. Offering different prices to potential customers based on trying to maximise how much they are able or willing to pay is, depending on your view, either smart business or exploitation.

To cast price segmentation in a benign light, you could say that it enables customers who would otherwise not be able to afford your product to enjoy its benefits, too, and you as a business gain another customer segment to sell to. For example, a cinema might offer student prices and thereby access a big contingent of customers who might otherwise not go to the cinema at all. Everyone is happy – except for the people paying full price for the same thing, but as long as the rules are clear and transparent, riots are at least avoided.

The twist is that traditionally you start with the full price – the price you have determined for your product such that you’re covering your costs and making a profit – and cut a bit off, risking cutting into your margin if there aren’t enough customers in the lower price range. What seems to be happening with Simple et al is that they start with a Fool’s Price and work their way down to the Full Price. You take no risk, because every price point above full price is super-high margin, so it’s all upside to you. And the rules are far from clear and transparent.

Be First to Comment